Adam Smith, Session 3: Choosing Duty

"Without this sacred regard to general rules, there is no man whose conduct can be much depended upon."

Next week, I will post the schedule for Part 2 of our Classical Wisdom series: "The Soul of Liberty." We will be reading Ralph Waldo Emerson, Leonard Read, and F.A. Hayek as we continue our inquiry into the conditions under which individuals and societies flourish.

With the tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk this week, we ask what we can do to prevent the ongoing degradation of civil society. Instead of “frantic tapping and swiping” on social media, Cal Newport urges us to “be a responsible grown-up who does useful things, who serves real people in the real world.” A study of the great works of Western civilization helps show the way.

Few of us will play a heroic public role, like Charlie Kirk played, in defending freedom. But when you understand Adam Smith, you know why the more private role each of us plays is no less critical. And with the senseless, sudden murder of Iryna Zarutska also freshly seared in our minds, we know that none of us is guaranteed to have more time to make better choices.

If we must accept Fate, we are not less compelled to affirm liberty, the significance of the individual, the grandeur of duty, the power of character.—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Near the end of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith tidily expresses what he has been helping us reconcile: “the great division of our affections… into the selfish and the benevolent.” As Smith has been showing us, our unbridled state of moral consciousness can create tricky situations, as we feel pulled in two directions. Perfectly selfish people may be miserable, but perhaps they don’t feel conflicted.

Smith, as Ryan Hanley put it, wants us “to find a way to live that allows us to realize both sides of our nature, our concern for ourselves and our concern for others.” As we come to the end of our three sessions on Adam Smith, let’s remember that Smith discourages us from resting on our good intentions. Hanely captures Smith’s urgency:

What really deserve our praise and admiration are not the warm feelings we can feel in private or in a passive state, but the “action” and “exertion” that take effort and energy. And Smith leaves no doubt that the work will be hard, telling us in the line that follows that someone who wants to live up to this will have to “call forth the whole vigor of his soul” and “strain every nerve.” Living this sort of life will not be for the faint of heart.

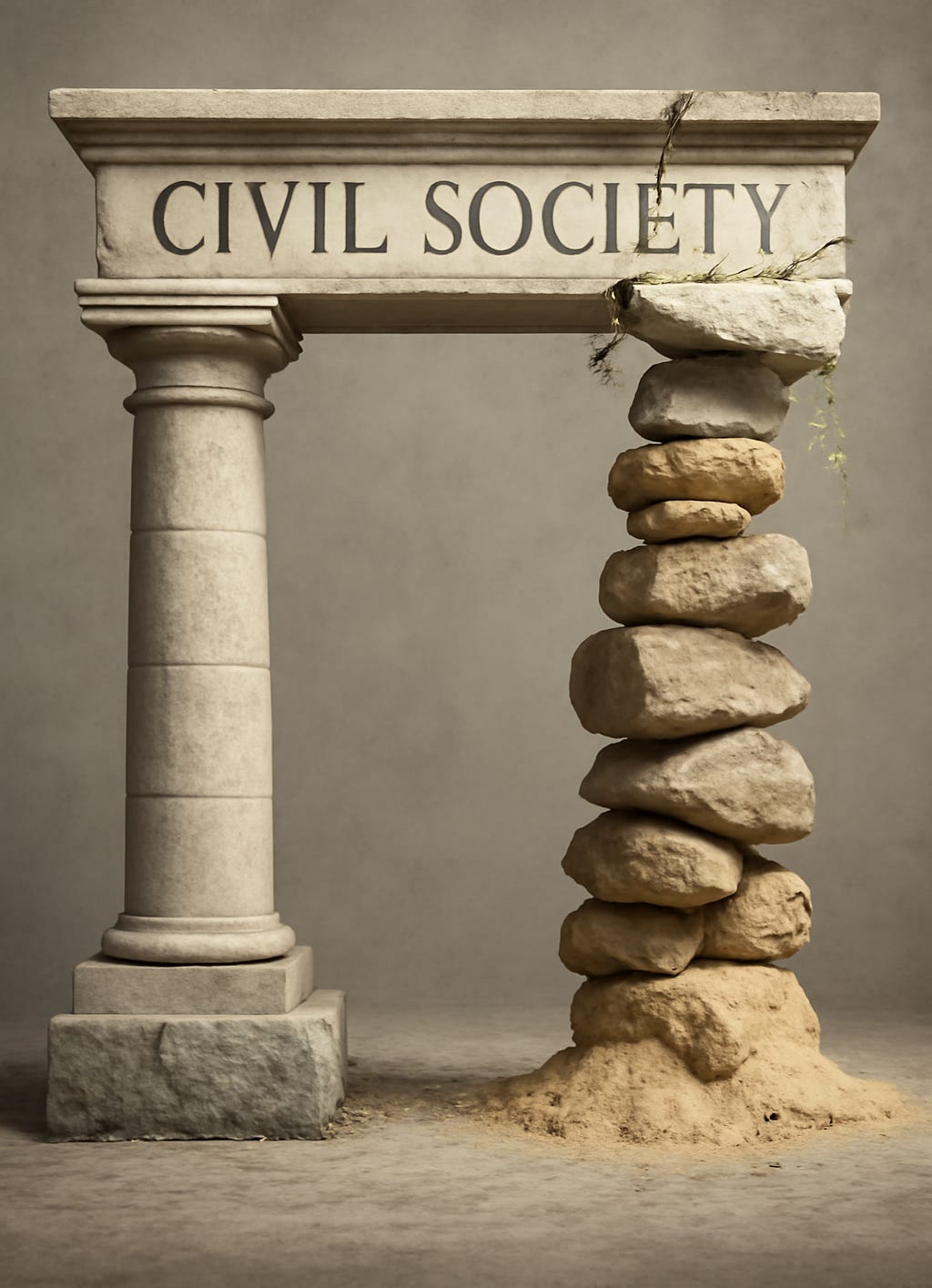

We must “strain” because the survival of our civilization depends on our willingness to call forth our “soul.”

By now, from our previous studies at Mindset Shifts U, we know that our feelings are faulty guides to our actions, and Smith agrees. He says our moods, our inclinations, and our passions are just fundamentally unreliable. One day, you feel a human connection to all you meet: the next day, you're grumpy and irritable. If we try to build our lives and society on those shifting sands, we are unlikely to be satisfied with the outcomes. Then, not pleased with the outcomes, we blame others for our own moral failures.